Final Girls Week: Death Proof

Final girls took over slasher movies in the early 70s creating a sub-genre that has seen them dealing with a multitude of bleeding limbs, chainsaws, car crashes, flying knives, and emotional tragedy through the years. When Carol J. Clover theorized the history and distinctive traits of the final girl in her book “Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the modern horror film” in 1992, the actual term ‘final girl’ was introduced and a list of very defined attributes was forever linked with the female protagonists in slasher movies.

The ideal final girl is a girl next door type, she doesn’t hang out with guys let alone doing drugs, usually the only person in a group of people that has an immaculate moral compass and can eventually outsmart the killer and save herself. A final girl saves herself because of her integrity and privilege, another major detail if we think about the fact that there’s nowhere near as many black final girls (or characters in slasher movies that don’t get killed straight after the opening credits for that matter) as there are white.

The girl that survives the killer in the first movie, also usually ends up butchered right at the start of the first or second sequel simply becoming another prop covered in blood. Regardless of what’s going to happen in the sequels though, the birth of the final girl meant a disruption in the traditional horror movie narrative structure, which ended up shifting a whole genre of films. At last, a character fully developed psychologically, able to think for herself, and even kill to save herself. Cool, right?

Here comes into play the killer. The male lead character that has one mission and one mission only: kill in the most brutal and random way possible. Usually a loner with some sort of psychological trauma that even Freud would struggle with.

Once the killer has picked his prey, there’s not too much anyone can do about it, and so we as an audience start experiencing the story from his point of view, up to the point where the final girl comes in guns blazing and saves herself, shifting the perspective again. Who in their right mind is still cheering for the killer at the end of the movie?

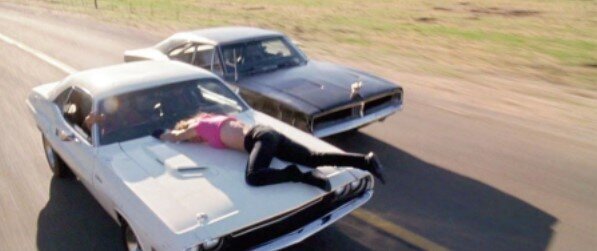

Enter Tarantino’s Death Proof and how three girls disrupted the whole final girl trope while riding a “970 Dodge Challenger with a 440 engine with a white paint job from Vanishing Point”. As per typical Tarantino fashion, Death Proof is classified as a slasher movie, but in reality, deviates from the theme so many times that it ends up being in its own category much like Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction.

Stuntman Mike is the not so evil presence that goes around dressed like an actual stuntman from the 70s, a huge scar on his face (that will make you wonder what the hell happened there) wearing a flashy jacket that we find sitting at a bar, drinking virgin pina coladas. He is creepy but nowhere near as creepy as Freddie Krueger’s butterface and manicure combo or Michael Myers staring silently at you from the distance. When he first interacts with Jungle Julia (and her legs), Arlene and Shanna everything seems almost normal. Mike gets to have a personal lap dance from Arlene as well, which technically makes her the final girl, but this is Tarantino. The way Stuntman Mike is presented to us as a human being instead of a monster leads us into sympathising for the poor bastard. So when the first car crash (or killing) happens, the adrenaline that builds up while the girls are singing a Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich’s tune we can’t help but look away, exactly like driving past a car accident in real life, we can’t help but stare in a mix of terror and admiration. Even Arlene, who was supposed to save herself according to the canon, ends up with a wheel on her face. If this was a classic slasher movie we would definitely be weeping at Jungle Julia’s legs flying around like chopsticks, right?

But it’s during the second half of the movie that Tarantino’s ability of fucking around with cinema precisely collides with what a modern-day final girl should look like. Zoë (the actual Zoë Bell, playing a version of herself) is an experienced stuntwoman, visiting her best friend Kim, also a stuntwoman), Abernathy, a makeup artist, and Lee, an aspiring actress. They also have multiple encounters with Stuntman Mike, who has now moved to Tennessee after a few broken bones. He’s now on the hunt for new flesh and can’t help himself but purposely bump into Abernathy’s feet (what else?), inadvertently making her yet another final girl.

The happy bunch gets down to it when the girls play Ship’s mast, where Zoë is strapped on the hood of the car and Kim is speeding in a dusty countryside road. Stuntman Mike and his “I’ve got an overcompensation problem” car appears out of nowhere and after chasing the girls for a while seems to just get over it and move on. What kinda bloodthirsty horror movie killer would do that? But it’s only when Kim shoots him out of the blue that the whole dynamic shifts. Suddenly Stuntman Mike is crying like a little baby and trying to escape and the girls, unscathed, are now doing the chasing. Despite crying out that she was scared just a few minutes before, now Zoë is riding the dodge like a chevalier on her steed with a metal pole in one hand, telling Kim to go faster.

Suddenly our final girls are in a position of power, not afraid and feeling seriously pissed off with our killer. Furthermore, they leave us confused because we really don’t know who to root for anymore. I mean Mike’s ugly cry was pretty convincing!

Finally when the way the girls get their revenge over Mike and his car is not as subtle as in other slashers. The girls are not scared or grateful to someone else for saving them; they’re beating the shit out of Mike in a gang beating that reminds you of the best spaghetti westerns, leaving the audience surely satisfied but also slightly dubious. If this is not the type of final girl I'd love to see more around then I don’t know what is. But yet again, this happened in a weird intersection between the Tarantino and Rodriguez universes so..

What, in my opinion, makes the movie even more special in regards to how final girls and women are fundamentally treated is the introduction of another group of ladies, called China Girls. The women appear in the end credits of Death Proof in an extensive series of photos with bright colours and colour palettes next to them, as they were used when professionally processing film and prints, to compare colours on the film and make sure that everything looked as it should. China Girls, or Sherley cards, have been around since the 1920s but gradually went out of fashion past the 80s.

China Girls were usually used for a multitude of films at the time, sometimes a long series of girls would accumulate at the end of a film, turning them into laboratory artefacts and thus stripping them of any type of physical existence. These endless series of girls on cards have always been out of the viewer's view since they’re either at the beginning or the end of the film, leaving some sort of mystery around them. Being brought and incorporated into the movie (Arlene doubles up as the final girl and one of the china girls) Tarantino once again goes against cinema rules and shows something that’s not supposed to be shown, shining a light on these girls that no one has ever paid attention to before and creating a bridge between China girls and final girls. At the end of the day, they kinda have the same life. They live inside the movie they’re in and regarded as objects only to be replaced later on or even reused in the following movies.

It might be a coincidence (especially when it comes to Tarantino and exploitation movies) but I feel like Death Proof is a great example of women literally stepping out of their character tropes and twisting a genre that way too often overlooks women or even worst, doesn’t even consider them worthy of getting out of a killing spree alive. Removing the genre rules from the equation lets us see what could really happen if the final girl could actually fight back and kick-ass as opposed to being a damsel in distress struggling for survival. It’s almost the end of 2020 after all.